Claudio R. Salvucci

Research Interests

Pennsylvania dialectology and dialect geography

Papers (Coming Soon)

Language in New Jersey: A History in Documents

The Savanna Jargon: A Remnant of the Lost Erie Language?

New Jerseyans Speaking Southern: the Down Jersey/Pine Barrens dialect

Major Publications

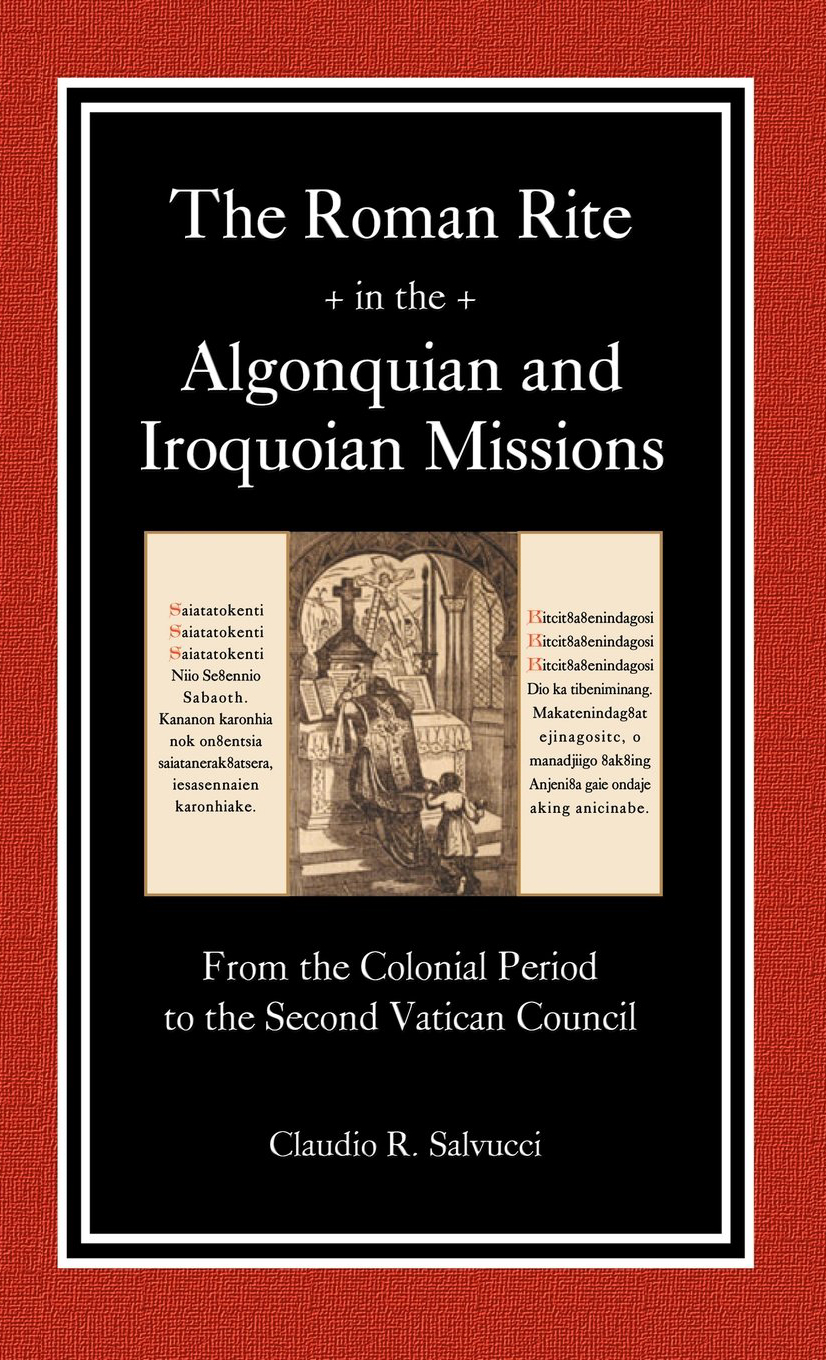

The Roman Rite in the Algonquian and Iroquoian Missions (2008)

Women in New France (2005)

Iroquois Wars I & II (2003)

American Languages in New France (2002)

Languages of Classical Antiquity Series (1998-2005)

A Dictionary of Pennsylvanianisms (1997)

The Philadelphia Dialect Dictionary (1996)

American Language Reprint Series (1996-2009)

Grammar of the Philadelphia Dialect (1995)

Native American Liturgy

Background

During the 1600s, French Catholic missionaries adapted the Latin Mass to the Indian missions that they served, translating the most common hymns and prayers into native languages for the Indians to sing during Mass. Over the following centuries, as the native scholae learned more of the official chants of the church, there developed full-fledged American Indian liturgical uses, based on the Roman Mass but with their own unique Mass propers sung in the vernacular, along with the ordinary chants like the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei. By the mid-1800s a number of these American Indian liturgies were being printed in paroissiens (parish-books) for the benefit of the mission Indians both in the pews and in the choir lofts.

These unique liturgies went almost forgotten in the liturgically turbulent years after Vatican II, and thus there has been little scholarly work on them. Almost all we have to go on are the texts themselves.

My Research

These liturgical texts are still badly in need of translation by expert Algonquianists and Iroquoianists, which is made more difficult by the fact that some of them are in archaic dialects quite different from their modern counterparts. But as no translations have yet been published, I have relied on my own fragmentary ad hoc interpretations combined with an in-depth knowledge of the ancient Roman Mass to closely analyze the paroissiens and reconstruct what the liturgy might have looked like at each mission.

My first major breakthrough came about through studying the introits of the Kanesetake Use in the Kaiatonsera Teieriwakwatha. There I discovered that just two of them accounted for nearly the entire liturgical year. The Teiotenonhianiton, based on the Roman Terribilis est for the dedication of the Church, was used in the penitential seasons of Advent, Septuagesima and Lent, as well as for the Sundays after Pentecost. The Aete8atsennoni , based on the Roman Gaudeamus, was used for festal seasons such as Christmas and Easter. A third introit is also given for some Masses of Our Lady: the Tek8anoronk8anions, based on the Roman Salve Sancte Parens. This discovery then made sense of other less detailed books that only listed three or four Introits in a row under the Latin headers Terribilis, Gaudeamus, and Salve Sancte Parens, without any further context of how they were used. A review of the manuscripts on which the printed works were based on, shows that this particular liturgical arrangement is an old one that goes all the way back to the early 1700s.

The use of Akwesasne and Kahnawake, on the other hand, does not seem that old but is much more fleshed out and highly developed. There, dozens of different Introits were in use. Typically these were Mohawk versions of Roman Introits, though sometimes assigned to different Sundays. And rather than using just one introit for saints, Akwesasne lists 10 “common” Masses for Apostles, bishops, martyrs, confessors, virgins, etc.

A great deal more research needs to be done on these liturgical traditions, well beyond what I am capable of contributing. But I hope, nevertheless, to bring them to the attention of a wider scholarly audience so that they can finally get the attention they deserve from liturgical scholars.

Product successfully added to your cart.View Cart

-

The Roman Rite in the Algonquian and Iroquoian Missions

$39.95This volume is the first ever book-length treatment of the distinctive American Indian Catholic liturgies of the Northeastern Woodlands. It compares and contrasts the Indian Masses of different missions with each other and with the official Roman Missal. It also contains chapters on the calendar and hagiography of the missions; formulas for Baptism, Matrimony, and other sacraments; the Divine Office; characteristic sacramentals and devotions; and religious life. The first book of its kind, and a must for scholars of Native American Catholicism.OUT OF STOCKThe Roman Rite in the Algonquian and Iroquoian Missions

$39.95This volume is the first ever book-length treatment of the distinctive American Indian Catholic liturgies of the Northeastern Woodlands. It compares and contrasts the Indian Masses of different missions with each other and with the official Roman Missal. It also contains chapters on the calendar and hagiography of the missions; formulas for Baptism, Matrimony, and other sacraments; the Divine Office; characteristic sacramentals and devotions; and religious life. The first book of its kind, and a must for scholars of Native American Catholicism.OUT OF STOCKThe Roman Rite in the Algonquian and Iroquoian Missions

$39.95OUT OF STOCKSuccessfully Added to your Shopping CartAdding to Cart...