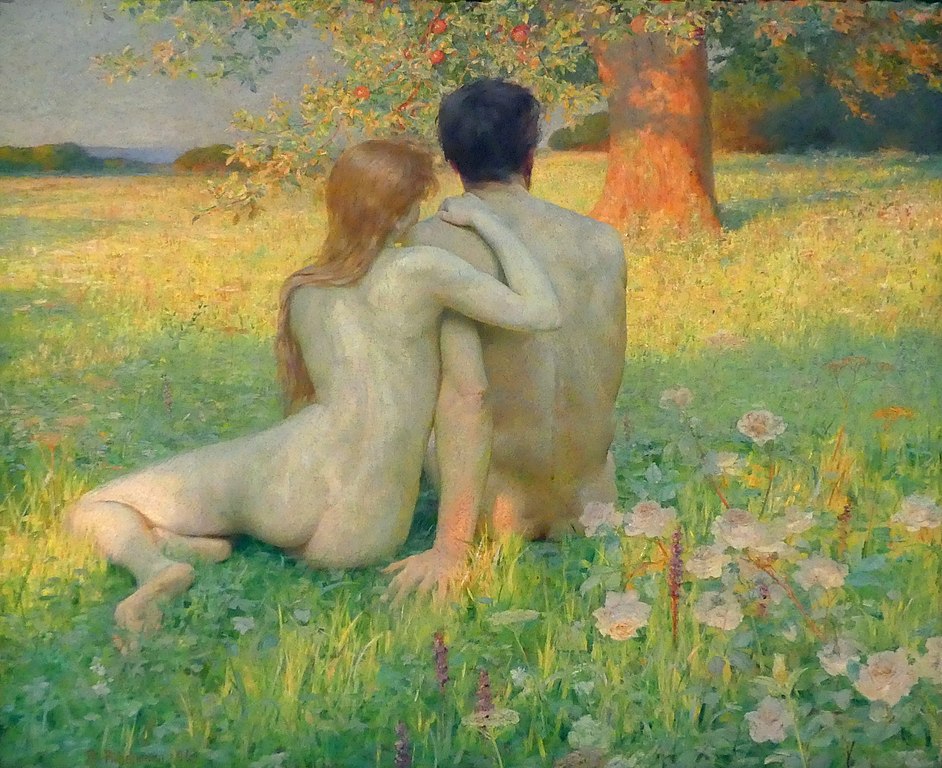

A Week of Adam & Eve

There is a whole week dedicated to Adam and Eve in the classical Roman liturgy, and it started yesterday, on Septuagesima Sunday.

This theme isn’t very well known at all, probably because it only appears in the traditional Divine Office recited by priests and religious. The Mass during this period shows no obvious connection with Creation and the Fall—so even a daily Communicant wouldn’t experience it without praying the Office.

Nevertheless, as the Divine Office is in fact the other half of the sacred liturgy, it would be well for us lay Catholics to be aware of how the themes of creation and Adam and Eve are explored this week.

In the traditional liturgy, Matins on Septuagesima Sunday began its nine readings with the incipit: “Here beginneth the book of Genesis“.

This day thus bears the distinction of being the beginning of the Biblical year. Of course, the books of the Old Testament are not read in order of occurrence in the church’s liturgy—they are read in thematic order according to their prophetic application to the liturgical season. Nevertheless, the Matins readings do show a loose Biblical arrangement, from Genesis in January/February to the minor prophets in November.

Septuagesima Sunday marks the beginning of that framework. On that day, the first Nocturn (a set of 3 lessons and responsories in Matins) begins with the following three lessons:

First Lesson: Days 1 and 2 of Creation. The creation of light and its separation from darkness, and the creation of the firmament and the separation of the waters.

First Lesson: Days 1 and 2 of Creation. The creation of light and its separation from darkness, and the creation of the firmament and the separation of the waters.- Second Lesson: Days 3 and 4 of Creation: The gathering of the seas, appearance of dry land, and the growth of plants; and the formation of the heavenly bodies, the sun, moon and stars.

- Third Lesson: Days 5 and 6 of Creation: creation of the fishes and birds; creation of the beasts and man.

The Office readings of Septuagesima Sunday are thus explicitly dedicated to the Hexaemeron, the six days of creation. They are neatly arranged two to each lesson.

Again, we don’t see this same emphasis in the Mass texts, or for that matter even in the other hours of the Sunday’s Office. Nevertheless, as far as Matins is concerned, it would be entirely appropriate to call Septuagesima “Creation Sunday”.

In fact, throughout the whole following week after Septuagesima, the Matins lessons continue to narrate the story of our first parents and their progeny:

- Monday

◦ Lesson 1: the blessings and dominion given to mankind

◦ Lesson 2: The seventh day of rest

◦ Lesson 3: Animation of man and formation of Eden

Tuesday

◦ Lesson 1: Placing of man in the garden, tree of good & evil

◦ Lesson 2: naming of the animals

◦ Lesson 3: making of Eve

Wednesday

◦ Lesson 1: The Serpent, temptation & fall

◦ Lesson 2: Nakedness & hiding before God

◦ Lesson 3: cursing of Adam and Eve

Thursday

◦ Lesson 1: Cain and Abel’s birth and offering

◦ Lesson 2: Murder of Abel

◦ Lesson 3: Flight of Cain

Friday

◦ Lesson 1: Descendants of Cain to Tubalcain

◦ Lesson 2: the birth of Seth to Adam and Eve

◦ Lesson 3: Generations of Adam, and Adam’s Death

Saturday

◦ Lesson 1: The Patriarchs from Mahaleel to Methuselah

◦ Lesson 2: Enoch and Methuselah

◦ Lesson 3: Lamech and the begetting of Noah

Although the Lessons progress chronologically through Genesis, through the five days of Creation well before Adam and then well into his descendants to Noah, the responsories accompanying each lesson keep returning to Adam.

For example, the very first responsory for the 1st and 2nd days of creation begins: “In the beginning God created the heavens and earth, wherein He made man also, after His own image and likeness“, and the penultimate responsory to Saturday’s lesson on Enoch and Methuselah is: “Behold, Adam is become as One of us, to know good and evil…“

For example, the very first responsory for the 1st and 2nd days of creation begins: “In the beginning God created the heavens and earth, wherein He made man also, after His own image and likeness“, and the penultimate responsory to Saturday’s lesson on Enoch and Methuselah is: “Behold, Adam is become as One of us, to know good and evil…“

Thus, the sacred liturgy keeps the week’s focus decidedly on Adam, whether it is narrating the very beginning of creation with him in view, or chronicling his descendants with him in hindsight.

All this structure was effectively eliminated in the most recent liturgical reform. Although Genesis 2 appears on the Mass of the First Sunday of Lent in the new Mass, it is read only every third year, and it does not set the tone for an entire of week of Office readings and antiphons as the old liturgy did.

I believe its absence has been felt, consciously or not. And that is perhaps why there have been modern attempts to “reliturgize” the creation narrative. That is not at all a bad idea in itself—after all, the traditional Roman liturgy did it already—but it seems to me it would be better to simply restore that old tradition, instead of reinventing something for the purpose.

In conclusion, it might well be asked–why does Matins choose Septuagesima, out of all other possible Sundays–as “Creation Sunday”? The answer is found in the Easter Vigil: here, for the only time, we finally see the Creation account read at Mass, as the first Prophecy.

However, if we were hoping for some time to meditate on it, we would be quite disappointed. Genesis is only the first of 12 prophecies read during the Easter Vigil, and that’s right at the heart of the busy Paschal Triduum. Our focus is fixed on the dramatic Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Our Lord. There can be no question of this apparently tangential reading demanding very much of our attention.

The vigil’s Prophecy, however, can and does serve as a liturgical reminder in the context of the Passion and Resurrection. A reminder of how we got to this point, and why Calvary was needed in the first place.

To ensure that the Paschal mystery has the most impact when we finally arrive there, it is important to have already meditated on Creation and the Fall beforehand. And there is no more appropriate Sunday to do that in, than the one when we first turn our gaze to Calvary.

This week, Matins will show how Adam and Eve fall ignominiously out of Eden. Part of our spiritual preparation this Lent is to bear that ever in mind, and to remember that we fell with them. In that knowledge, we sorrow, we hope, and we patiently endure.

Until Holy Saturday, when Christ will gloriously lift them back to Paradise, and beckon us there as well.

Saints Adam and Eve, pray for us!

-

←→

Lent Prayers and Devotions

$5.99Spend your Lent profitably with this handy collection of prayers that you can carry in your pocket wherever you go. These excellent devotions from traditional sources will keep your focus on Christ crucified and help stir up a lively repentance and contrition for your sins.- Buy 5 at $5.00

- Buy 10 at $4.75

- Buy 30 at $4.50

Maximum quantity exceededMinimum purchase amount of 0 is requiredLent Prayers and Devotions

$5.99Spend your Lent profitably with this handy collection of prayers that you can carry in your pocket wherever you go. These excellent devotions from traditional sources will keep your focus on Christ crucified and help stir up a lively repentance and contrition for your sins.Lent Prayers and Devotions

$5.99Successfully Added to your Shopping CartAdding to Cart... -

←→

Passiontide Prayers and Devotions

$5.99As your Lenten observances intensify, you will appreciate this collection of devotions that will keep your focus on Christ crucified. Carry it in your purse or pocket wherever you go! We've brought together numerous beautiful prayers from traditional sources that will take you through the final two weeks of Lent and Holy Week.- Buy 5 at $5.00

- Buy 10 at $4.75

- Buy 30 at $4.50

Maximum quantity exceededMinimum purchase amount of 0 is requiredPassiontide Prayers and Devotions

$5.99As your Lenten observances intensify, you will appreciate this collection of devotions that will keep your focus on Christ crucified. Carry it in your purse or pocket wherever you go! We've brought together numerous beautiful prayers from traditional sources that will take you through the final two weeks of Lent and Holy Week.Passiontide Prayers and Devotions

$5.99Successfully Added to your Shopping CartAdding to Cart... -

←→

The Zacchaeus Tree

$29.95Drawing from the rich Byzantine tradition, Lynne Wardach has compiled decades of teaching, crafting, cooking, and teaching catechism into a book to help Catholic families make the Lenten climb toward heaven.Maximum quantity exceededMinimum purchase amount of 0 is requiredThe Zacchaeus Tree

$29.95Drawing from the rich Byzantine tradition, Lynne Wardach has compiled decades of teaching, crafting, cooking, and teaching catechism into a book to help Catholic families make the Lenten climb toward heaven.The Zacchaeus Tree

$29.95Successfully Added to your Shopping CartAdding to Cart... -

←→

Stations of the Cross by St. Alphonsus Liguori

$5.99A timeless classic! One of the most beloved devotions for Lent is the Stations of the Cross, and few versions are as popular as the one composed by St. Alphonsus Liguori. This edition includes 14 engravings you can meditate along with the images of each Station even if you are standing still in a pew, at home, or traveling. Also includes the verses of the Stabat Mater that are often sung between each station.- Buy 5 at $5.00

- Buy 10 at $4.75

- Buy 30 at $4.50

Maximum quantity exceededMinimum purchase amount of 0 is requiredStations of the Cross by St. Alphonsus Liguori

$5.99A timeless classic! One of the most beloved devotions for Lent is the Stations of the Cross, and few versions are as popular as the one composed by St. Alphonsus Liguori. This edition includes 14 engravings you can meditate along with the images of each Station even if you are standing still in a pew, at home, or traveling. Also includes the verses of the Stabat Mater that are often sung between each station.Stations of the Cross by St. Alphonsus Liguori

$5.99Successfully Added to your Shopping CartAdding to Cart...

St Katharine Drexel: Visitation of the Navajo Mission of St. Michael

St Katharine Drexel: Visitation of the Navajo Mission of St. Michael

St Katharine Drexel: Visitation of the Navajo Mission of St. Michael

Prayers for the United States

- Buy 5 at $5.00

- Buy 10 at $4.75

- Buy 30 at $4.50

Prayers for the United States

Prayers for the United States

American Saints Book of Prayers

- Buy 5 at $5.00

- Buy 10 at $4.75

- Buy 30 at $4.50

American Saints Book of Prayers

American Saints Book of Prayers

Immaculate Conception Prayers and Devotions

- Buy 5 at $5.00

- Buy 10 at $4.75

- Buy 30 at $4.50

Immaculate Conception Prayers and Devotions

Immaculate Conception Prayers and Devotions

American Devotions 3 Booklet Set

American Devotions 3 Booklet Set

The Little Office of Baltimore

Lasance Initials Font

Lasance Initials Font

Lasance Initials Font

Triduum of the Martys of Auriesville

- Buy 5 at $5.00

- Buy 10 at $4.75

- Buy 30 at $4.50

Triduum of the Martys of Auriesville

Triduum of the Martys of Auriesville

Novena in honor of the North American Martys

- Buy 5 at $5.00

- Buy 10 at $4.75

- Buy 30 at $4.50